MS Estonia - Part 1

On Sept 28, 1994, a passenger ferry from Estonia to Sweden sank in the middle of the Baltic Sea, along with 852 souls. But what was officially explained as the tragic result of a defective bow design was, in fact, a massive NATO coverup.

This is the story of the MS Estonia.

The Day of

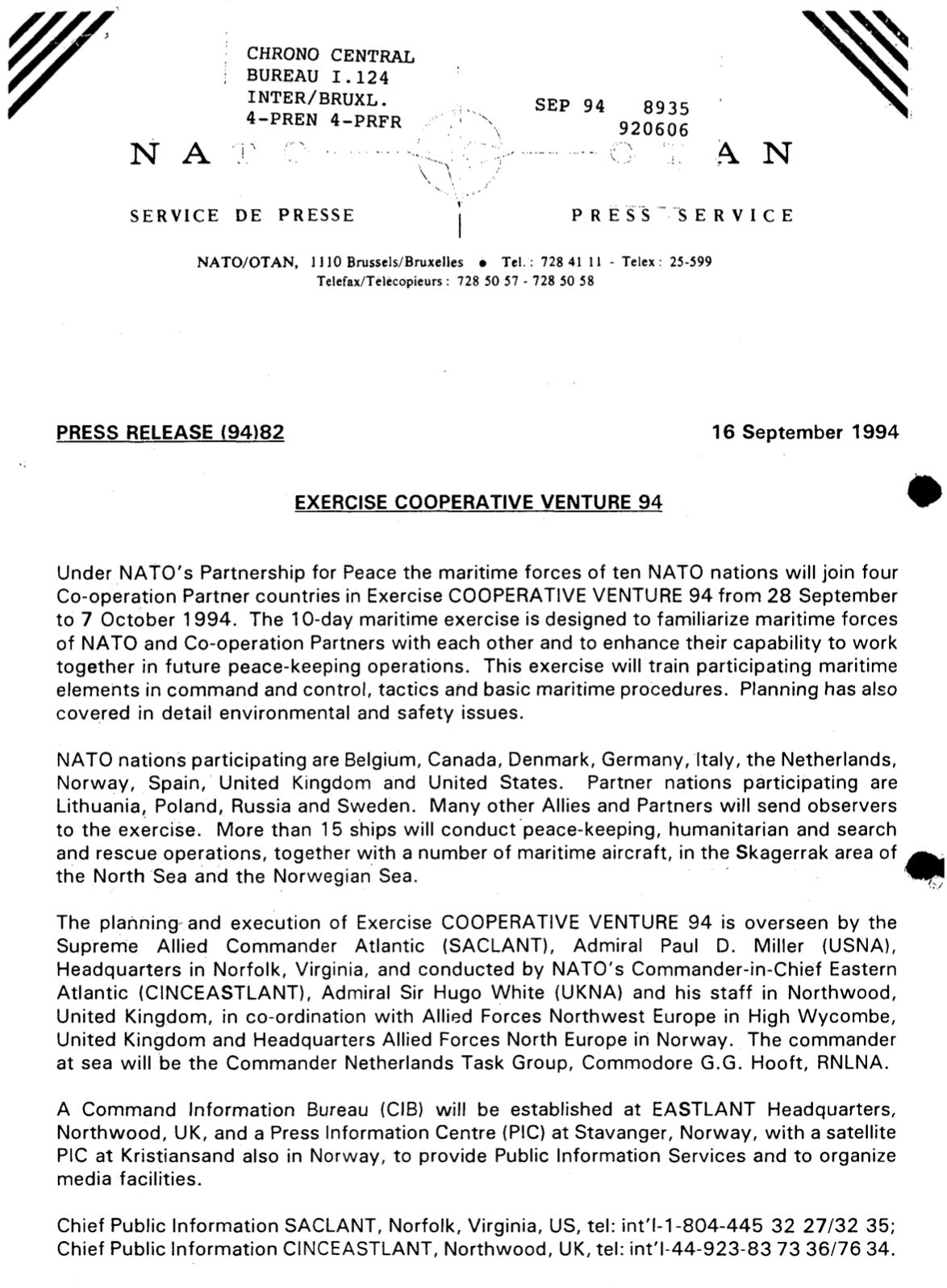

On Sept 27, 1994, NATO military assets assembled around Norway for a naval military exercise called Cooperative Venture 94, the first “Partnership for Peace.” The exercises involved 15+ ships and several maritime aircraft prepared to conduct search & rescue operations.

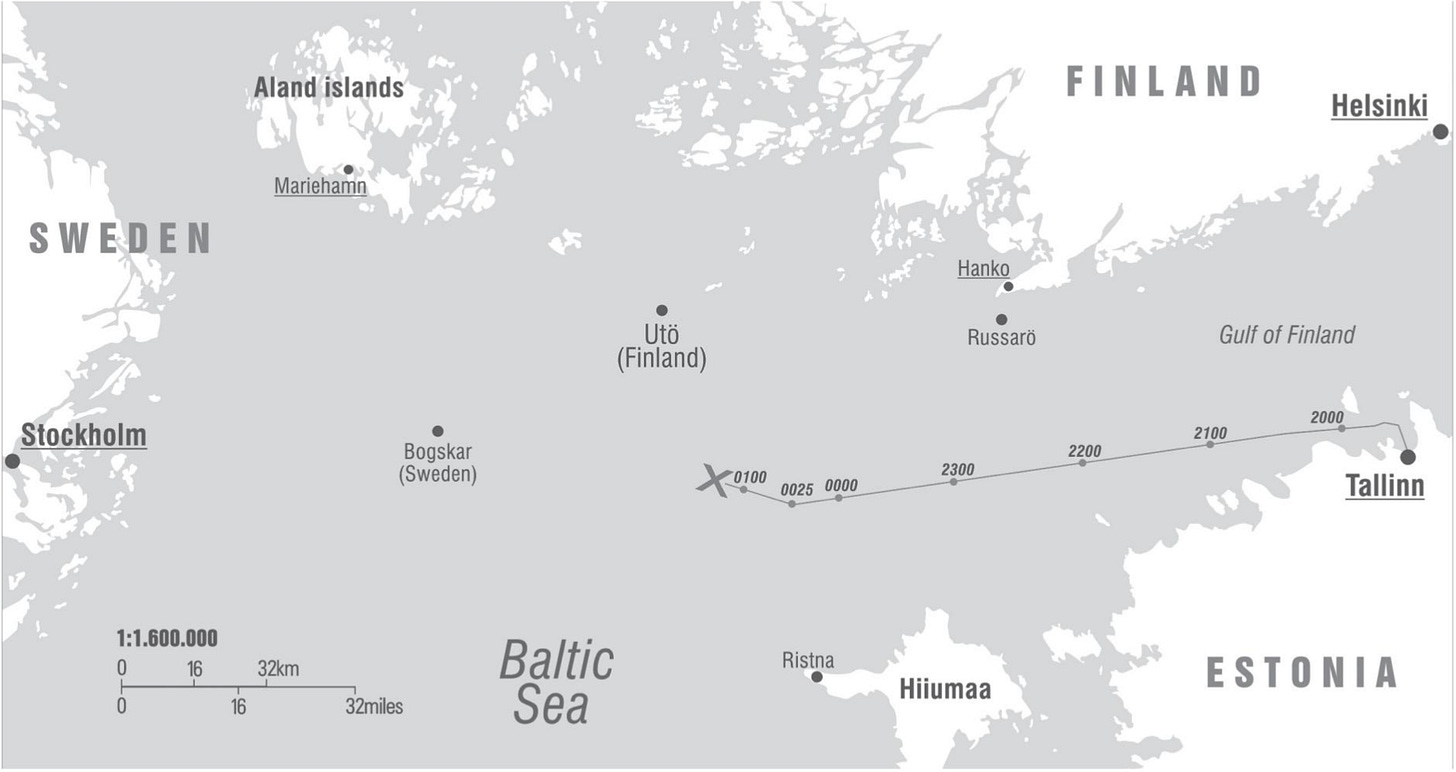

That same day, vehicles and passengers in the Estonian city of Tallinn loaded onto the MS Estonia. They departed at 19:15, bound for Stockholm with 989 people on board, 803 of them passengers. The overnight journey typically took approximately 15 hours.

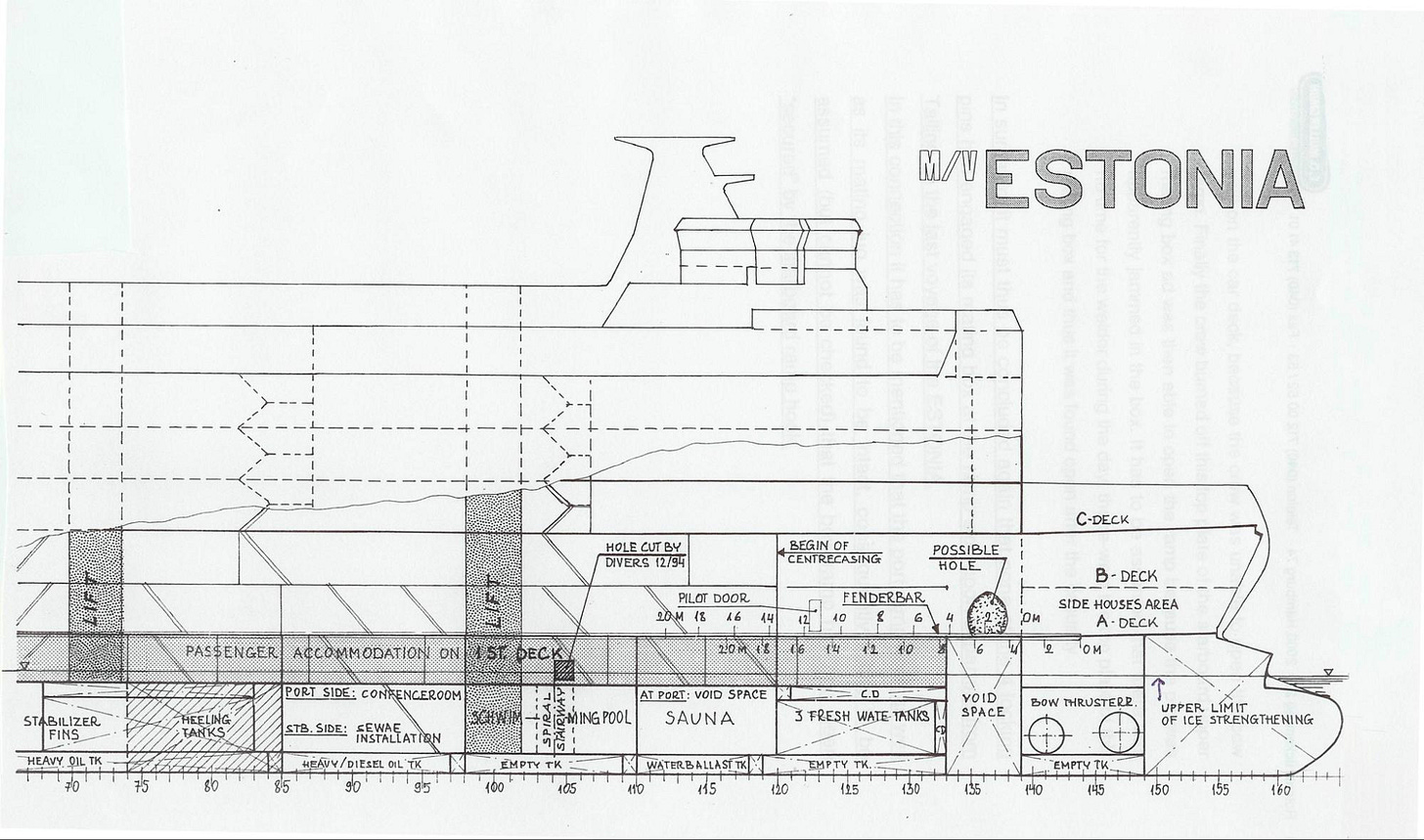

The ferry was large, with a total length of 157 m and nine decks. The ship’s internal passageways were labyrinthine, with long corridors and stairwells leading to dead ends. The lowermost deck, below the vehicle decks, was occupied by sleeper cabins.

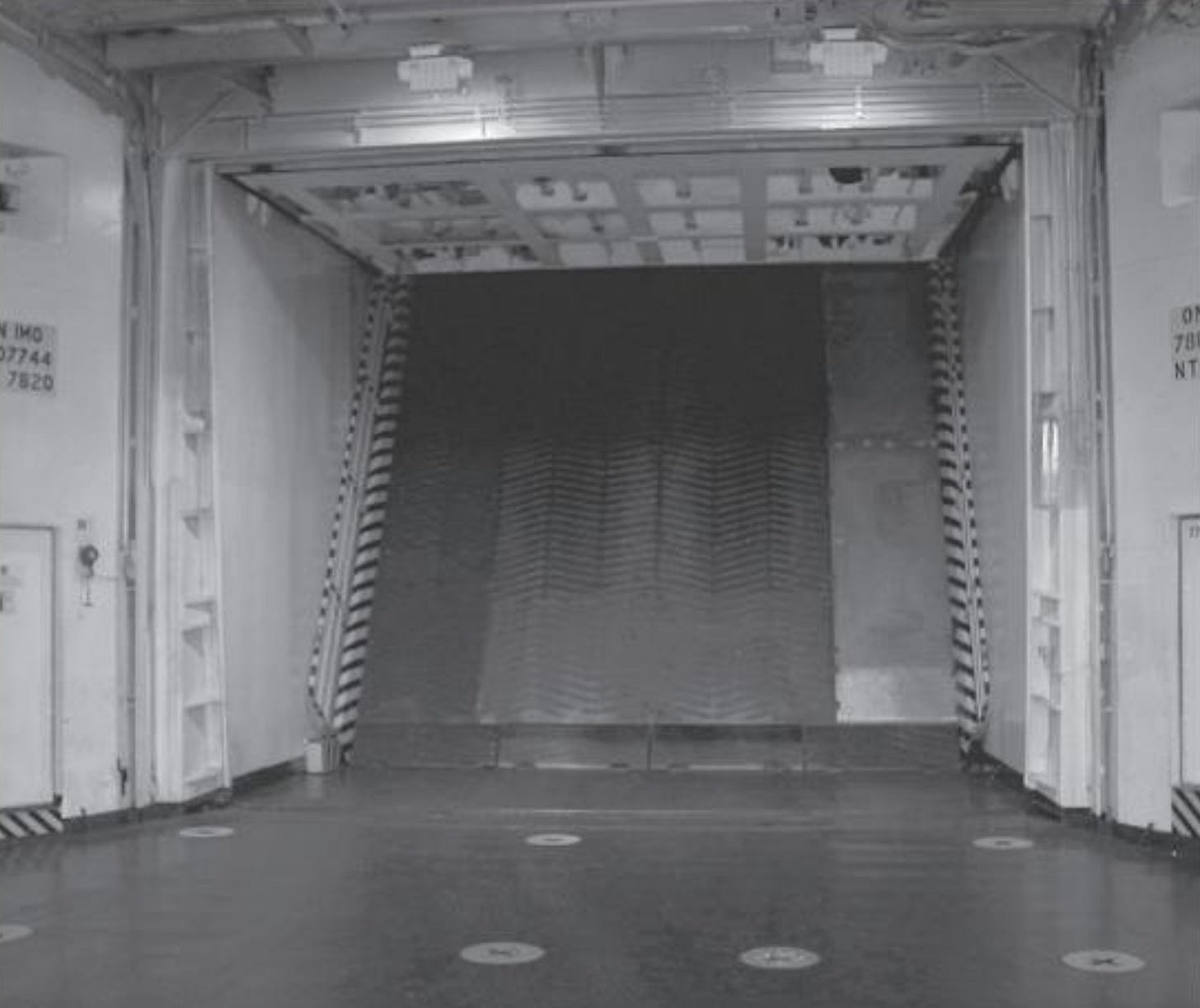

Cars loaded the ship’s vehicle decks via a ramp at the bow. A bow visor concealed the ramp during the voyage. The ramp rotated upwards during loading and lowered and locked into place during transit. The ramp provided the primary watertight seal.

Initially, sailing conditions were moderate but soon became rougher once the ship reached open seas. Although a storm generated high winds from the southwest (50–60 km/h) and large waves (3–4 meters), conditions were in no way unprecedented for the North Baltic Sea.

At 01:02, passengers were awoken by a loud metallic bang followed by an abrupt heel to starboard. The bang was reported by several survivors, particularly those who were in the sleeper cabins on Deck 1 at the time. One survivor even reported being thrown from their bunk.

.The bang was accompanied by scraping, as though the ship was moving through ice. Some witnesses assumed the ship had run aground. Survivors reported that after the sudden heel to starboard, the heel relaxed to a stable “list” (ie. persistent tilt) of ~10°.

Many survivors who were on Deck 1 (below the vehicle deck) during impact reported seeing water coming up from *below* Deck 1. A few minutes later, the list again increased, this time more slowly and steadily over the next 15 minutes.

Between 01:22–01:24, two distress calls were received over the emergency radio frequency by a nearby ferry. On the mayday call, Estonia’s navigator reported the ship had developed a bad list, which he estimated to be 20 - 30° to the starboard side.

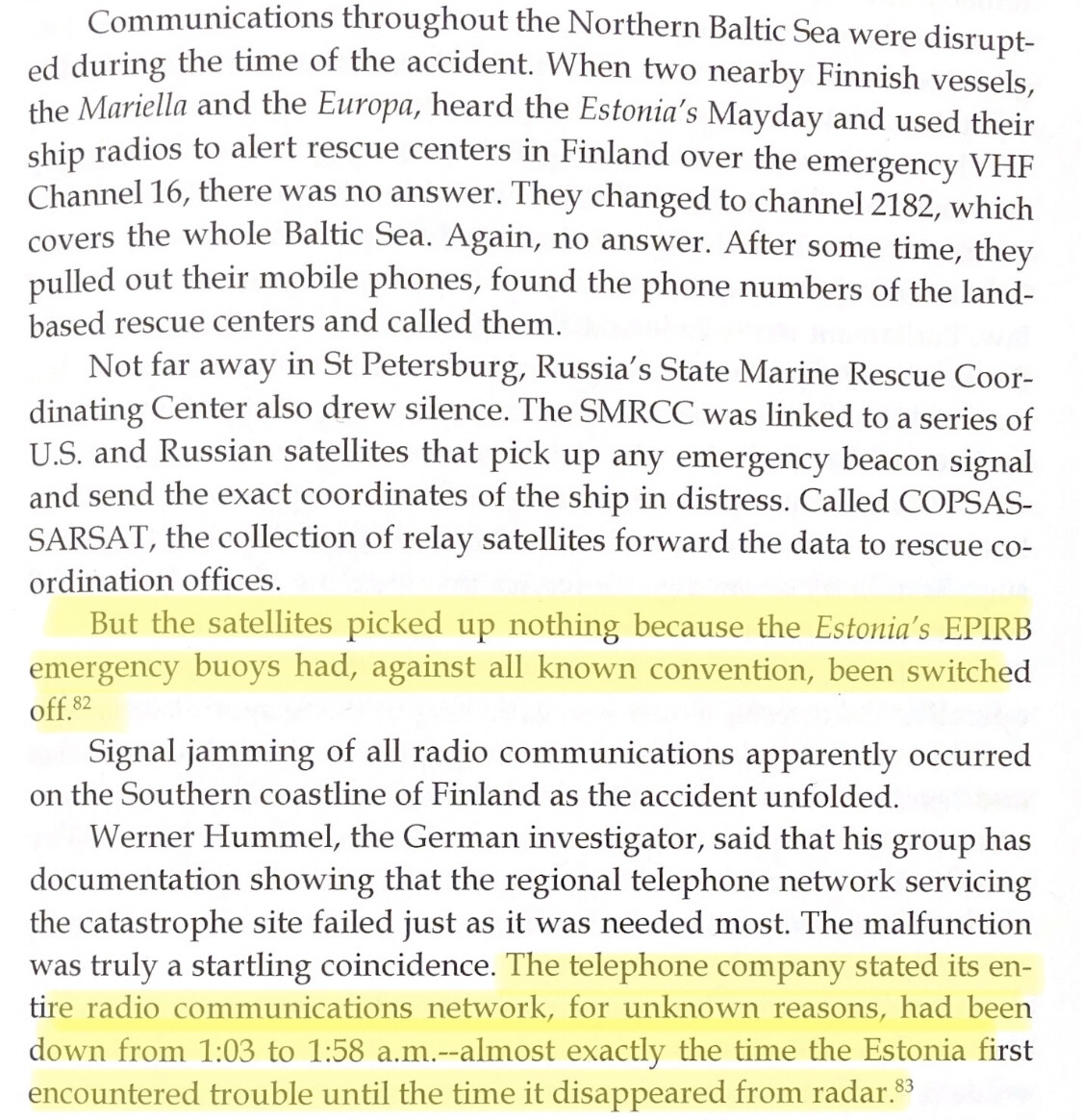

However, as the accident unfolds, there are indications the mayday calls are being jammed, as are all radio communications throughout the Northern Baltic Sea. The regional telephone network also inexplicably goes down for an hour at 01:03, just a few minutes after the loud bang.

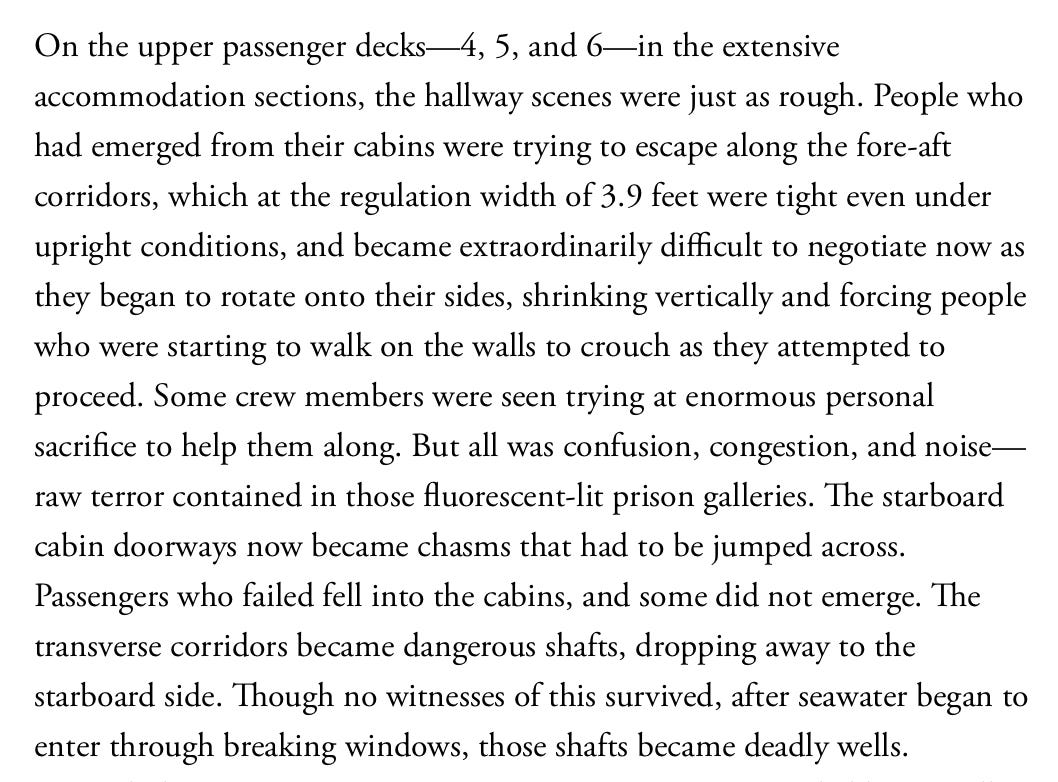

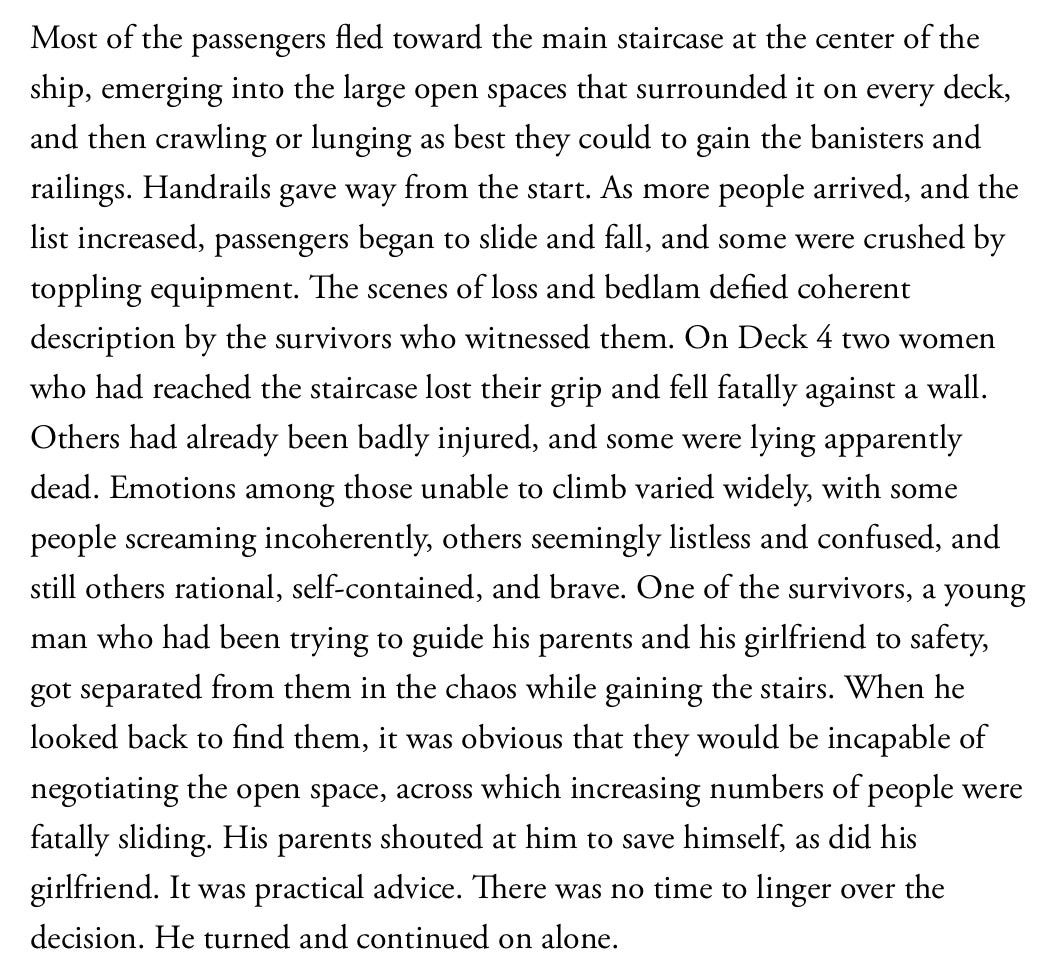

30 minutes after the loud bang, the ferry’s list had increased to 60-70°, making it easier to walk on walls than the floor. However, the rapidity of the listing and the labyrinthine corridors made escape extremely difficult. The ship’s corridors quickly became death traps.

Due to the rapidity of the sinking, lifeboats aren’t launched. Instead, life rafts are haphazardly thrown into the water, forcing people to jump into the 10°C stormy seas. Those unable to swim to a raft and climb aboard perished.

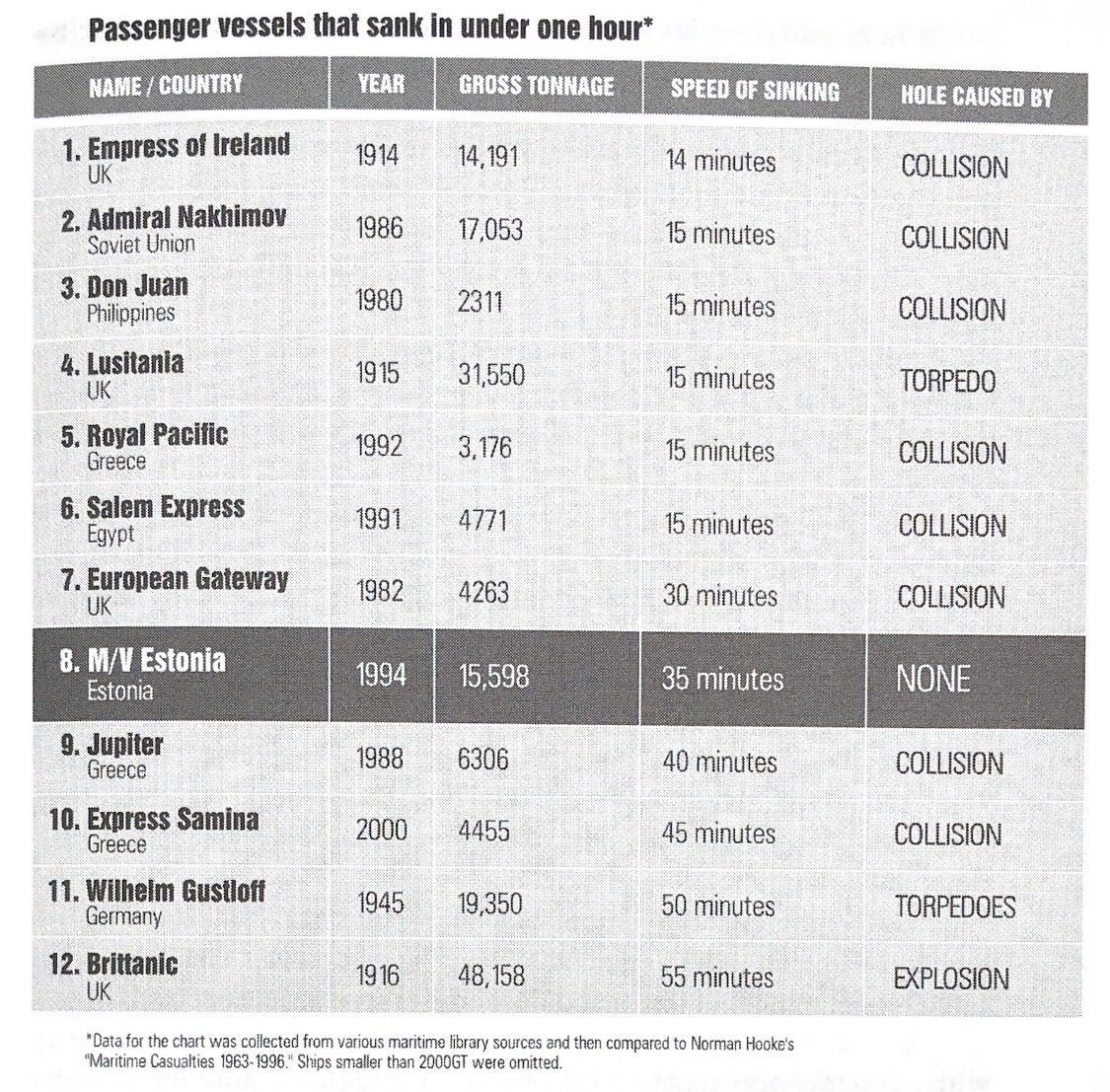

The Estonia sinks in less than an hour, a speed that has only ever been seen in ships with hulls torn open by collisions or torpedoes. Yet, despite the battalion of NATO naval forces assembled within an hour’s flight time of the ferry, none assisted with the rescue.

Rescue

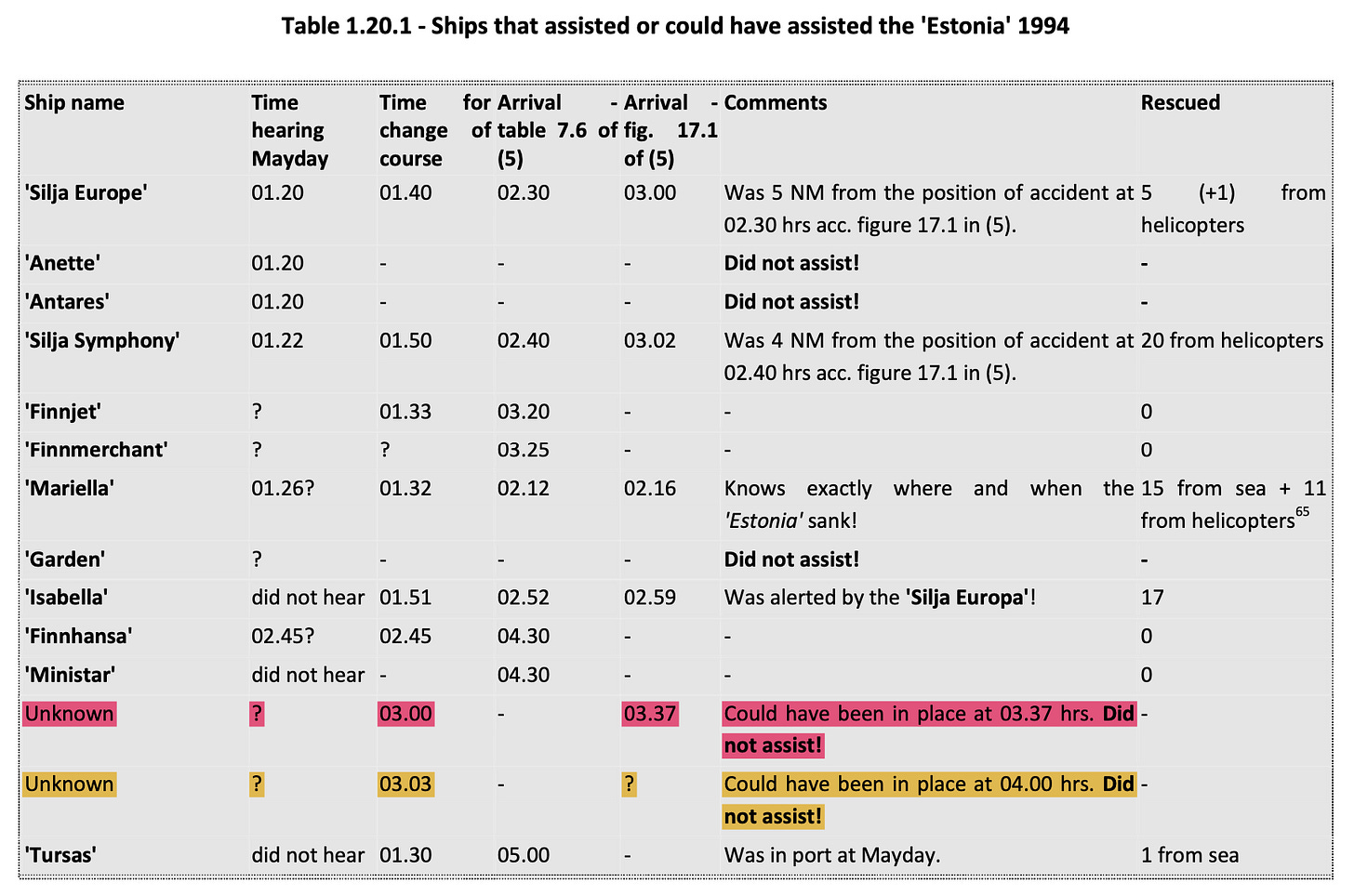

8 nearby ships hear Estonia’s mayday, but only 5 redirect to help. Utö, a Finnish radar station 50 km to the north, records ship positions as they head toward Estonia’s last radar reflection. Two unknown vessels 11-13 km east of the Estonia’s position never assist and disappear.

Signals from emergency locator beacons (EPIRBs), which should have deployed automatically, were never received, despite the beacons being checked to be in full working order only a week prior. These buoys relied on direct communication with the Cospas-Sarsat satellite network.

Helicopters don’t arrive until 2 hrs after the distress call is received. 138 people were pulled from life rafts by helicopter and boat, with 1 later dying in hospital. In total, 852 people perished, making it Europe’s deadliest peacetime maritime disaster in the 20th century.

Official investigation

The morning of the sinking, and before any formal investigation, the Swedish PM Bildt ordered the Swedish Maritime Administration (SMA) to investigate bow visors on other ferries because “a construction fault may have caused the accident.”

Three surviving crew members were interviewed about what they saw on the morning of the rescue. One of the crew initially said he saw a leaking but closed ramp, but later adjusted his story to claim he didn’t see the ramp directly, only via video monitor.

On the day after the sinking, Russia extended an offer to Sweden’s UD (Ministry for Foreign Affairs) to help rescue any potentially alive passengers trapped in the wreck, who may have been able to survive in air pockets for up to a week after sinking. Sweden never responds.

The Prime Ministers of Estonia, Finland, and Sweden soon met and agreed on a coalition investigation into the sinking, forming the Joint Accident Investigation Commission (JAIC). However, it soon becomes apparent that there is an informational hierarchy and Sweden is at the helm.

Shortly after, the head of the Swedish Maritime Administration (SMA) publicly criticizes Swedish Prime Minister Bildt and is forced to resign. His replacement was Johan Franson, the SMA’s Chief Legal Officer.

A week later, a new Swedish government takes over from Bildt. The new government puts Ines Uusmann, the Minister of Communications, in charge of the investigation. However, it becomes clear that Uusmann relies entirely on Franson for information.

Search for the bow visor

On Sept 30, Finnish vessels conducted a sonar scan of the wreck and found evidence that the ship’s bow visor is still partially attached, or at least resting directly on the wreck's bow. But the bow visor is missing when the first official ROV returns video on October 2.

On October 18, the JAIC announced that it had found the bow visor a mile west of the wreck. The 56-ton visor is raised a month later and brought to shore to be scrutinized by the commission. This scrutiny forms the bulk of the commission’s analysis of why Estonia sank.

The official theory is that locking bolts holding the bow visor in place failed due to wave impacts. But when divers recover a crucial bolt from the bow visor and bring it to the surface for investigation, the Swedish navy commander throws it back into the sea.

But a 2021 review of the bow visor found unequivocally that the extensive damage present on the visor could not have come from mechanical impact forces alone. Instead, the damage must have been, in large part, the result of explosives.